April 5, 2021

The story of Badas and Booms begins around the time that Dulce Shimkus noticed the constant hum in her early childhood classroom. At St. Joan of Arc Catholic Preschool in Phoenix, children ages 4 and 5 painted and played. “I felt like our classroom had a heartbeat,” she said. “It was inherently musical.”

As part of the Collaborative Planning Community of Practice professional development program, organized by Paradise Valley Community College (PVCC), Dulce began a journey to deepen her understanding of the words and work of young children. The program partnered Dr. Katherine Palmer (Katie), Curator of Education at the Musical Instrument Museum (MIM), with Dulce to exchange ideas and observations, make connections, reflect, and deepen understanding of how children learn.

“We wanted to pilot this program with a musical educator,” says Christie Colunga, Early Childhood Education Faculty at PVCC. “Katie spent time in Dulce’s room at St. Joan of Arc and observed and led sessions with the children. Dulce documented the sessions and what was happening when Katie was not there. Then together, they studied the documentation in sessions facilitated by Ana Stigsson, my colleague at the college.”

Through the process of studying documentation together, Dulce and Katie amplified children’s rights to experiences where they can interact and build relationships with sound, music, and one another – and children’s right to be seen as the protagonists in their learning.

What captured AzAEYC’s attention and interest in the Badas and Booms Project was that it affirms that young children have the capacity and capability to invent new forms of language that contribute to their self-expression.

Dulce and Katie reflect on the creation of “Badas and Booms” by the children, discoveries along the way, and how this collaboration furthered their own personal and professional growth.

Dulce

At the beginning, I read The Noisy Paintbox by Barb Rosenstock in class. I gave a small group of children large pieces of paper and played various musical compositions. I asked them to listen to and draw the music. The first musical piece I played was the theme from the movie Jaws by composer John Williams.

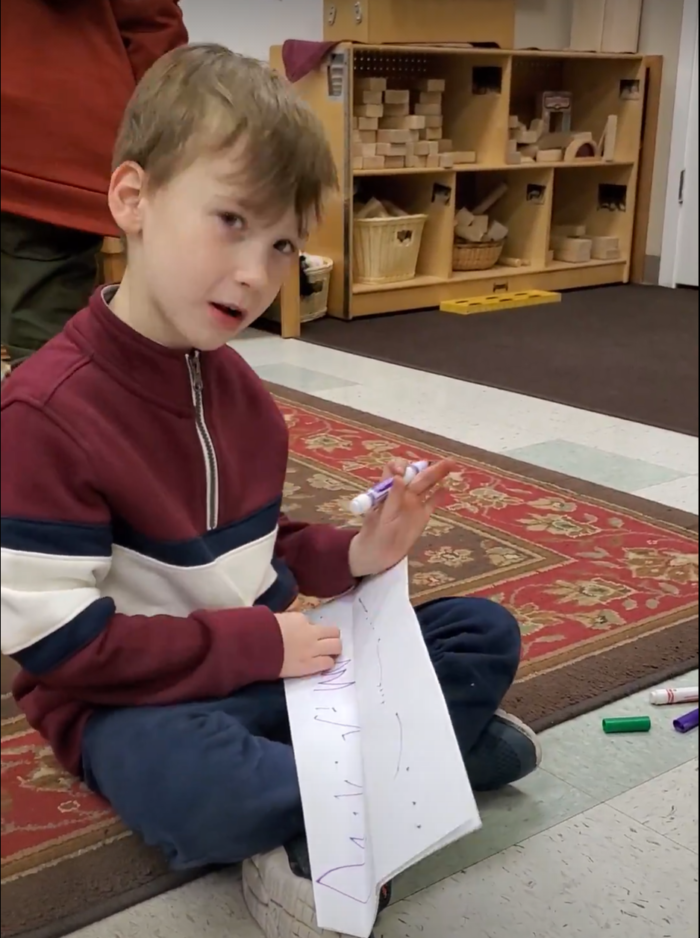

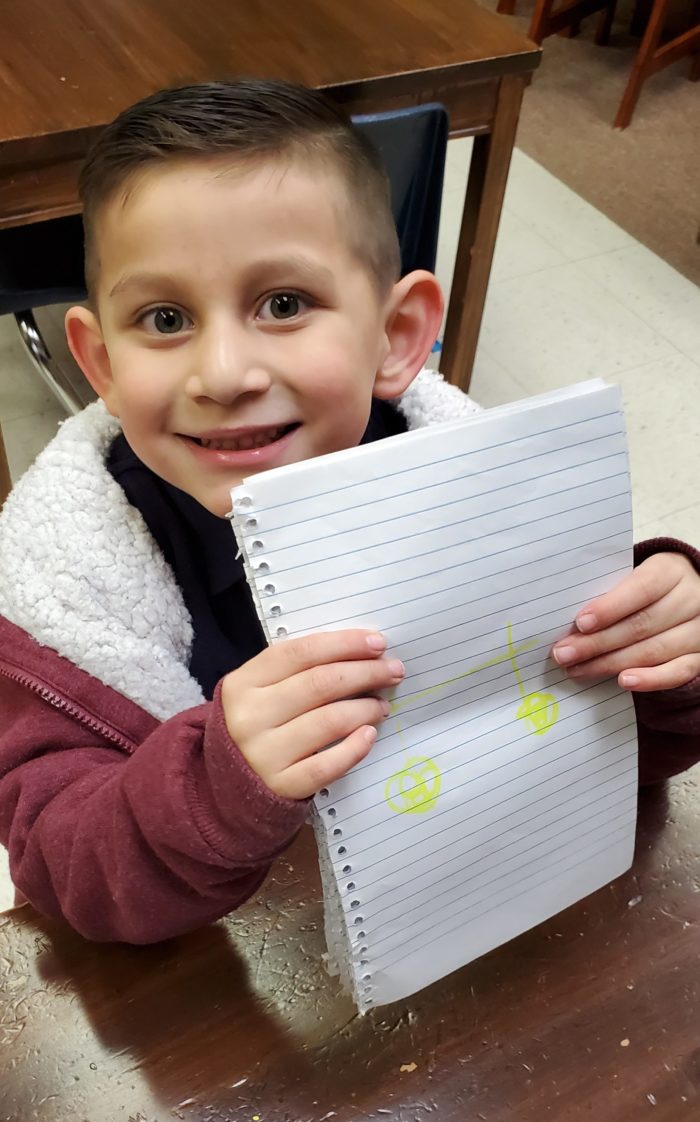

A few of the boys noticed the sounds “bada, bada, bada.” Then, I played the Star Wars “Imperial March.” Children noticed the rhythm and called it “boom boom boom, bada boom, bada boom.” I asked them how they would write those sounds and rhythms. Henry drew the first Badas and Booms. He wrote several rhythm sentences, and said, “Let’s put them together.”

Katie

It doesn’t always happen that an artist – musical or otherwise – is partnered with a teacher who is so well-attuned to what’s happening with children, who’s able to ask critical questions, and helps guide what we can do artistically.

Dulce was really a fantastic partner in this endeavor. We both set out with an initial question: how can we make the early childhood classroom more musical? I have this fundamental belief that children are inherently musical. We don’t always notice their musicality because, as we grow as adults, not all of us stay attuned to that music making.

Dulce

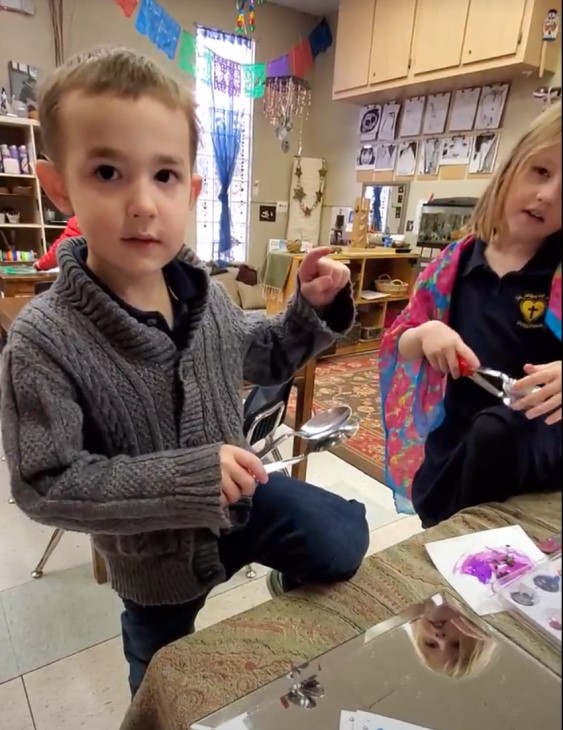

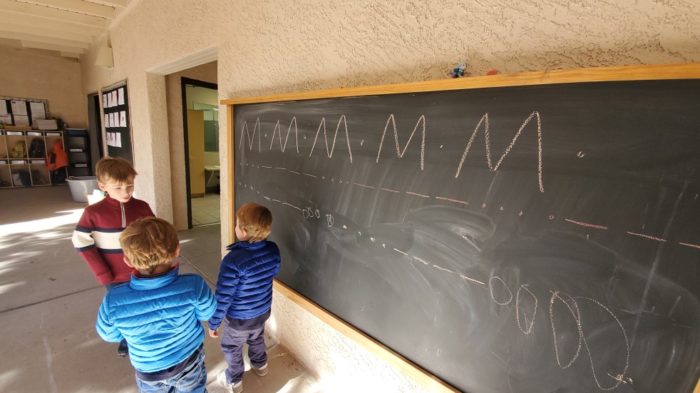

Katie came to St. Joan weekly. She offered scarves and feathers to the children along with musical activities. She began supporting their rhythm language by teaching them quarter notes, eighth notes, and rests. The children began combining the two sets of symbols in their writing.

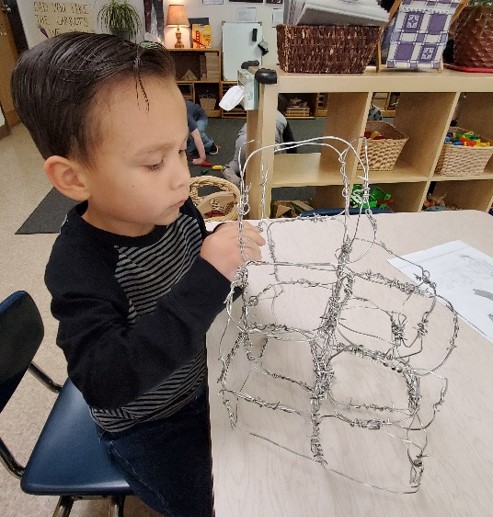

These are some of our musical instruments. The children used them respectfully. They were always available for their use.

Children developed the rhythms into characters and stories. “Running was running! He was chasing Bada.…. and Boom, Boom, Boom! Then Walking and Boom went to the park.” The children adjusted their actions and tempo according to the rhythm of their characters.

Katie

The idea of a rhythm language was emerging based on some of the activities Dulce previously set up. I knew of a great activity for rhythm and language development related to that concept. That’s how we ended up with children moving their bodies in “walk and running” patterns, which represent quarter notes and eighth notes. We also incorporated quarter note rests. What we discovered was that children were able to seamlessly synchronize the two rhythm languages and use them interchangeably.

It was so interesting to me that the children converted the two languages. As the project evolved, they moved back and forth between these two musical languages through the form of storytelling, the one they invented and the other – which is well-recognized in the field of music.

Dulce

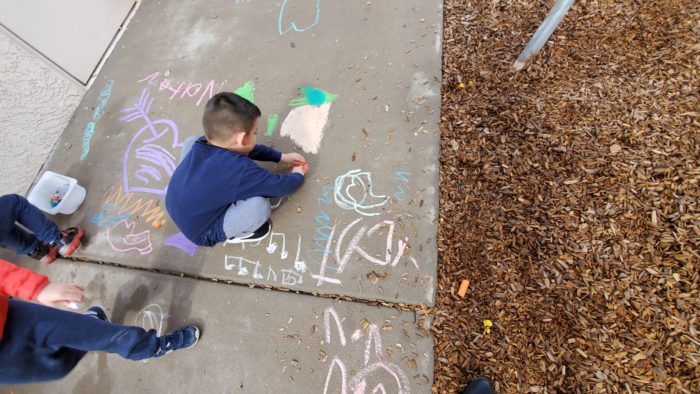

We sat on the floor, I played some music asked them to draw what the music sounded like. I purposefully played some musical pieces that had strong, noticeable rhythms. They started naming the sounds. I asked them, “How would you draw it?” They began teaching some of the kids in the other classes, telling them, “Oh, we have our own rhythm language. Do you want to learn?”

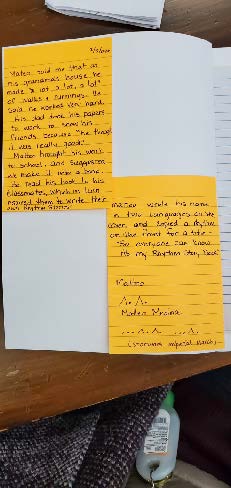

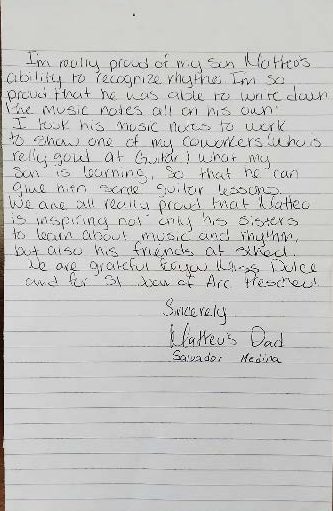

Matteo is a bilingual Spanish/English speaker. He realized how fluent he could be through the language of music and rhythm. Matteo wrote a story using “Walks and Runnings,” with quarter and eighth notes. It was pages and pages of notes. He brought it to class and was very proud of his work. He wanted to staple it together and add a cover. He signed his name with Badas and Booms, and added the symbols for the Star Wars “Imperial March” at the bottom. Matteo’s dad was very proud of his work and borrowed the book to show his co-workers.

Each of the symbols became a character in his story. “Walk went to the park. Running was his brother and went to the park too.” He read the story to the class, which in turn inspired many of his classmates to write their own rhythm stories.

Katie

Once the parents were able to draw a parallel between the eighth notes and the quarter notes with these Booms and Badas, they became much more attuned to just how musical their children were.

Being heard, especially when you are young and often unheard, can be a really powerful mechanism for self-confidence, and for your own self-determination as you move forward.

Dulce

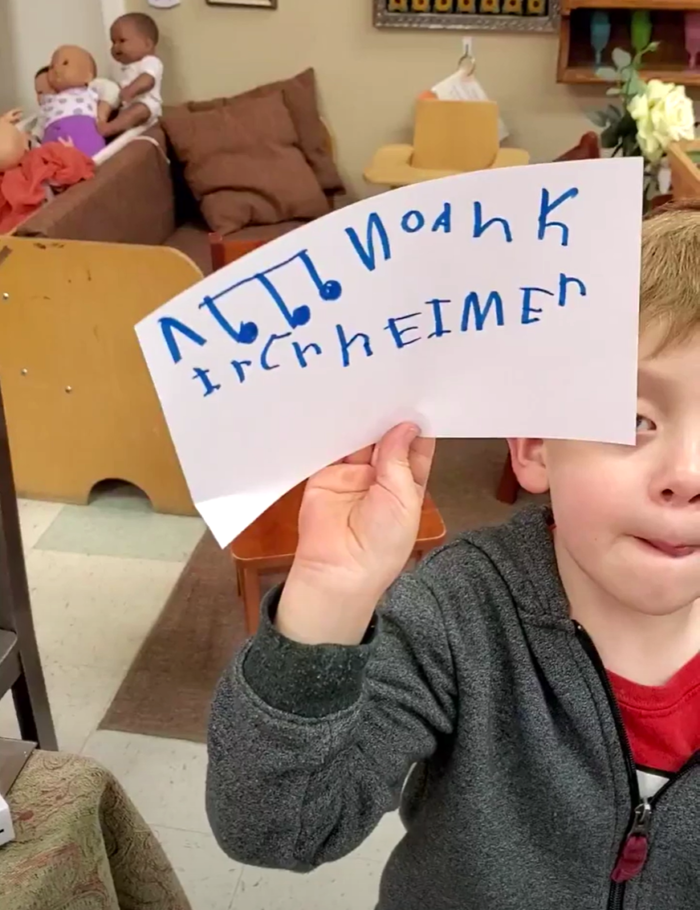

David’s initial verbal communications in class were often limited to responding with an “uh-huh.” I felt sad when he couldn’t make himself understood — he’d just quit. Yet he quickly became one of the protagonists of this project. He began writing his name with Badas and Booms, Runnings and Walks, as well as writing rhythm sentences.

He created a rhythm character puppet and he brought rhythm puppets into our clay area. His confidence grew so much! He noticed his own communication skills evolve, and he brought his parents into the classroom to show them our latest work. He was able to make himself understood in a multitude of ways in the classroom. To me, that was absolutely beautiful.

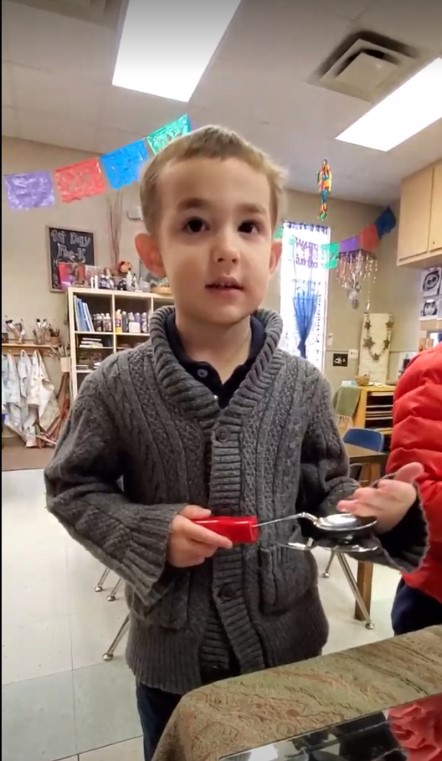

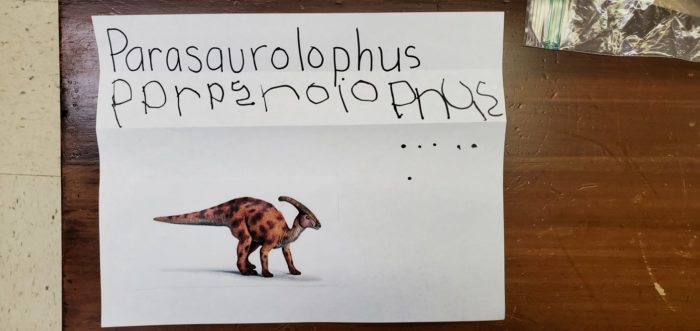

David had been carrying a little plastic dinosaur in his pocket for about a week. He wanted to know what its name was. I researched and found it was a Parasaurolophus. I reflected back on his communication using the rhythm language, and I asked him if he’d like to get the musical spoons to tap out the sound.

He did and broke down the sounds of the word by himself. He also figured out how to spell T-Rex. He beamed, “That’s amazing how I did that.” I got chills and a bit teary. David was proud of himself. I asked if he’d like to write the rhythm name down. He did but explained we needed a picture. I printed one and wrote the dinosaur name across the top. I thought he would write the rhythm name underneath the one I wrote. Instead, he started writing the letters then wrote the rhythm name. He wrote six Booms to represent the six syllables in Parasaurolophus.

David emerged as a storyteller in class. We had loose parts and clay available every day. We also had natural materials throughout our classroom environment. David brought loose parts and natural materials over to the clay table. He began telling incredibly elaborate stories. The other children joined in this storytelling. He was communicating his ideas and thoughts through the materials.

We didn’t see him shut down anymore when he couldn’t make himself understood. He was able to make himself heard in many new musical ways. This was absolutely one of the most beautiful things.

What began as a project to see how we could make our space more musical became an exploration in emergent rhythmic literacy. It was a beautiful thing! It was evident in every part of the classroom from blocks to clay to dramatic play – all woven together. It was seamless.

We were listening to African drum music in class.

Adrian held his hand to his heart and said, “My heart is a drum.”

Katie

I learn new things from children every single time I work with them. This Badas and Booms experience enhanced that. I have served as a music specialist in a variety of different settings. I rarely get to experience what happens in the room after I leave.

Music might be typically relegated to around 20 to 30 minutes of circle time. They do their music making, and then they go on with the rest of their day. Teachers sort of check that box in the schedule. We don’t always think critically as a group about what happens through the rest of the day, and I really believe some of that should be musically informed.

Dulce

Looking back, I noticed the confidence that the children gained through these experiences.

Katie

Children have the right to be heard and to be understood. If we don’t keenly listen — musically and otherwise — to what they are saying and notice what they’re showing us, then we’re not fulfilling our end of the relationship.

There’s a level of trust that comes with work like this. As we trust the children, we’re able to deepen our understanding and work together to make a truly collaborative learning space. Not just between teachers and artists or facilitators, but with the children themselves, because they helped guide this project.

Teachers have the right to collaborate – the right to collaborate with their community. And with artists. The right to collaborate is essential.

Dulce

Teachers have the right to be supported through reflective professional development. I think it’s really hard for us to do that sometimes because of program requirements and constraints. I’ve studied the work of the educators in Reggio Emilia, Italy and been inspired by their collaboration. Debbie Hilliard, the director at St. Joan of Arc, realized the potential of this work with Katie and the MIM. She made it possible to organize our time together. That program support allowed me to have the time as a teacher to prepare documentation, discuss and reflect with Katie and Ana, and study the children’s work together.

Teachers have the right to think and to be researchers of children’s work. When we work in this way, we see how amazing children are. Children are just incredible, if you stop and take the time to listen to them.

The Collaborative Planning Community of Practice professional development program is supported by funding from the First Things First Phoenix North Regional Partnership Council.