Substantial funding for child care is critical in this moment and in the recovery to come. In this letter to Arizona Governor Doug Ducey, Rhian Evans Allvin of NAEYC, Dr. Eric Bucher of AzAEYC, and Kelly Larkin of SAZAEYC offer an eight-step roadmap for relief and recovery that calls for state investment in a well-functioning child care system.

April 19, 2020

Dear Governor Ducey,

On behalf of the National Association for the Education of Young Children (NAEYC), the Arizona Association for the Education of Young Children and the Southern Arizona Association for the Education of Young Children, we would like to thank you for your leadership during the COVID-19 pandemic. These are trying times for the country and children, families, businesses, and communities are relying heavily on the leadership of Governors.

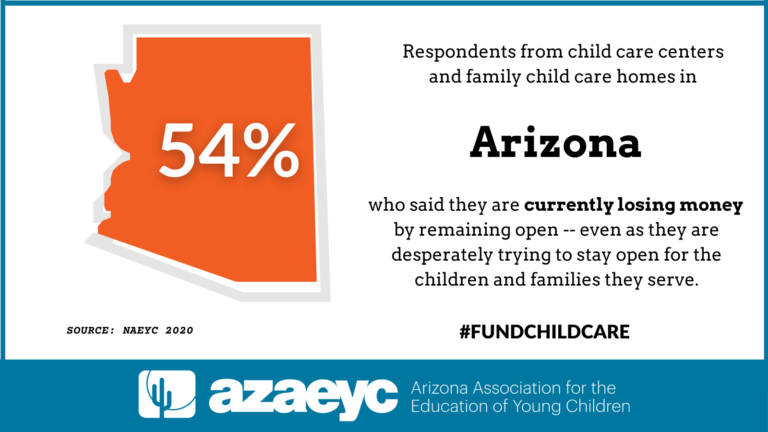

As you and many others have recognized, our country will not fully recover from this health and economic crisis without a robust support system for our child care programs, providers, and staff, who typically serve more than 12 million children birth through age 5 each day. With the support of members across the country, NAEYC has been working with Congress to ensure the broad spectrum of child care providers have the support they need to survive this pandemic, in the face of mass closures and dramatically decreased enrollment.

The Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act provides the $99 billion childcare industry with $3.5 billion in direct support through Child Care and Development Block Grants (CCDBG) and access to additional financing through Small Business Administration Loans (SBA) and increased Unemployment Insurance (UI). While these investments are important steps in the right direction, they rapidly are proving to be insufficient considering the scope of the crisis, the precarious financial position of child care, and states’ frequent, and appreciated, declarations of child care as an essential service.

Getting additional, necessary, and substantial funding from Congress is crucial, and depends in part on Governors spending the emergency CCDBG funds swiftly and wisely, prioritizing their quick deployment to child care providers — whether or not they previously have received public support for caring for low-income children, or whether they have stayed open to serve essential workers or closed for health, safety, or economic reasons.

As we work collectively to preserve child care in this moment and for the recovery to come, and in the spirit of cross-state cooperation that elevates innovative approaches based in state action, and reduces chaos for families and providers, we offer an eight-step roadmap for relief and recovery that can be built upon your state’s actions, and tailored to reflect states’ unique factors.

1. Spend the money now.

This is not the time to budget across months and years. This is the time to spend money as quickly as possible. While states have the option to spend funds over time, we strongly recommend the $3.5 billion in CARES Act funding be fully expended in the next three months. The funds can be distributed with flexibility and creativity to allow providers to pay mortgage and rent, payroll, and/or benefits.

2. Make CCDBG authorized in the CARES Act simple, efficient, and accountable.

We recommend a flat-rate biweekly or monthly payment where all providers who are eligible for CCDBG are eligible for funding, regardless of whether they were or currently are serving families receiving subsidies. Eligible programs include center-based programs and family child care homes; for-profits and nonprofits; programs that are closed and those that have remained open; those historically supported by government subsidies and those where families pay out of pocket; and the majority of programs whose financial structures depend on a combination of multiple funding streams.

To provide the support that allows for the kind of known survival capacity currently appreciated by K-12 and Head Start programs, the payments should be based on licensing capacity, not attendance or enrollment. States can direct the payments to cover fixed costs (mortgage or rent, utilities, employee benefits) and structure applications so they ask the minimum number of questions required to create appropriate accountability based on a demonstration of actual fixed costs. We estimate that those fixed monthly costs will range on average from $1500-$2500 for family child care to $15,000-$30,000 for center-based programs, depending on licensing capacity.

To confirm these costs and their contexts, the state needs to know whether programs are also receiving SBA loans, how much they typically receive in annual CCDBG subsidy payments, and the percentage of enrollment that is covered by subsidies vs. parent payments. Payments also should confer an expectation and establish a verification procedure to confirm that employees who are working in programs serving children of essential workers are compensated commensurate with their work during a public health crisis.

3. Ensure the CARES Act CCDBG, annual CCDBG, Small Business Administration funding, and unemployment insurance all work together.

During a crisis it is critical that government agencies effectively communicate internally and externally. In order for the child care system to weather this pandemic storm, it will take strong partnerships, proactive communication, and efficient planning and implementation by the Governor’s office and state CCDF administrators to unwind the complexities in unprecedented and challenging times.

States will further their own public health and economic goals if they relax income eligibility, provide technical assistance to child care programs applying for SBA loans, help providers navigate Unemployment Insurance for furloughed employees and ensure educators who remain on the job receive “heroes pay”.

4. Recognize early childhood educators who have continued to work through this public health crisis.

At a minimum, early childhood educators who are currently working should be paid at the same levels as those who are accessing increased unemployment insurance benefits. Given that the average child care worker makes only $10.70 an hour, the “heroes pay” could be large–and well-deserved.

5. Fast-track public health guidance and access to Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) to child care providers and staff.

For those providers that have remained open to serve essential personnel, their risk of contracting and spreading COVID-19 is no different than frontline employees in other essential fields. States can leverage the role of licensing staff to ensure these providers get ongoing daily public health support and guidance and immediate and sustained access to PPE including masks, booties and child care-appropriate cleaning supplies and protocols.

6. Lift income eligibility levels, but maintain existing licensing and regulatory requirements.

The law gives states flexibility in setting income eligibility levels, payment rates to child care providers, and parent copayments for ongoing CCDBG and CARES Act CCDBG funding. Within the guidelines of the law, it is critical that states provide the maximum flexibility to providers so they can pay their monthly bills without asking hard-pressed families to sacrifice scarce resources . Conversely, a public health pandemic is not the time to lift existing licensing and regulatory requirements to establish provisional care, allowing unprepared and minimally-qualified people to care for our children. Existing licensed providers can adequately meet the demand with the benefit of strong coordination.

7. Acknowledge part of the child care sector was left behind in the CARES Act SBA provision.

While more than 90 percent of child care providers are eligible to access SBA loans, some are multi-state providers with substantially more than 500 employees. These providers are an essential segment of the market, employing tens of thousands of early childhood educators and serving hundreds of thousands of families. While advocates encourage Congress to address this reality in the next relief package and through technical fixes in the current package, states should, in the meantime, ensure these providers are eligible for CARES Act CCDBG funding.

8. Leverage employers of essential employees.

Before COVID-19, more and more employers were recognizing the value of employer-sponsored child care at the worksite, by purchasing “slots” for their employees in community-based settings or providing back-up child care. While most sectors are suffering significantly during this public health crisis, others such as online food supply and delivery services are thriving and even expanding their businesses. We encourage states to ask these private employers to help finance child care so that they, too, have a stake in ensuring their essential employees receive access to quality care.

Our nation’s governors are making herculean efforts to protect the public from harm, support the health systems that are needed to fight this virus, address the severe economic impact on many businesses, and set the stage for a swift economic recovery. Child care is essential for each of these efforts. In fact, none of them can happen without a well-functioning child care system. Adults won’t go back to work and leave their children alone.

We ask that you give child care the investment, time, attention, and creativity required to get through this crisis and help our country get back on its feet. After all, high-quality child care is the foundation on which all other industries exist. We stand ready to assist as national and state partners, and are happy to discuss this eight-step roadmap with you, your Cabinet members, and staff.

Sincerely,

Rhian Evans Allvin, Chief Executive Officer

National Association for the Education of Young Children

Dr. Eric Bucher, Executive Director

Arizona Association for the Education of Young Children

Kelly Ann Larkin, Executive Director

Southern Arizona Association for the Education of Young Children